Comprehensive Management of Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata stands as one of the most psychologically challenging autoimmune conditions, affecting hair follicles and dramatically altering patients’ appearance and self-confidence. This chronic, organ-specific autoimmune disease primarily targets hair follicles through autoreactive T-cells, resulting in non-scarring hair loss where the hair shaft disappears but follicles remain intact, offering hope for potential regrowth.

The condition affects up to 2% of the global population, with prevalence appearing higher in children compared to adults (1.92%, 1.47%). While any hair-bearing surface can be affected, the scalp represents the most noticeable and distressing area of involvement. The rapid onset of hair loss in sharply defined areas creates distinctive patterns that experienced dermatologists can readily identify.

Understanding the Root Causes: Etiology of Alopecia Areata

Genetic Predisposition

Family history plays a crucial role in alopecia areata development, with affected individuals showing significantly higher rates of positive family history. Research has identified strong genetic associations, particularly with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes that regulate immune and inflammatory responses. These genetic factors explain why the condition often runs in families and why some individuals develop multiple autoimmune conditions simultaneously.

The Atopy Connection

An intriguing relationship exists between alopecia areata and atopic conditions like eczema, asthma, and allergies. Studies consistently demonstrate that alopecia areata in atopic individuals tends to manifest earlier in life and present with more severe, extensive hair loss patterns compared to non-atopic patients. This connection suggests shared inflammatory pathways between these conditions.

Autoimmune Mechanisms

The autoimmune nature of alopecia areata becomes evident through several key observations. Hair follicle autoantibodies appear in some patients, though their primary role remains unclear. More significantly, affected individuals show increased frequency of other autoimmune diseases, particularly autoimmune thyroid disease, myxedema, and pernicious anemia. This clustering suggests common underlying immune system dysfunction.

Environmental Triggers

Various environmental factors can precipitate alopecia areata episodes in genetically susceptible individuals. Infections, certain medications, physical trauma, and psychological stress have all been implicated as potential triggers. The stress connection appears particularly strong, with many patients reporting significant life stressors preceding their hair loss episodes.

The Hair Growth Cycle and Disease Pathogenesis

Normal Hair Growth Phases

Understanding normal hair growth helps explain how alopecia areata disrupts this process. Each hair follicle cycles through three distinct phases approximately 20 times during a person’s lifetime:

Anagen Phase (Growing Phase): At any given time, 80-90% of scalp hair follicles exist in this active growth phase, during which hair grows continuously.

Catagen Phase (Transitional Phase): This brief 2-4 week transitional period occurs as hair prepares to enter the resting phase.

Telogen Phase (Resting Phase): The final phase where hair follicles gradually release their hair shafts, making way for new hair growth.

Disease Disruption of Normal Cycling

Alopecia areata fundamentally disrupts this orderly progression. When the condition strikes, hair follicles in the anagen phase bypass the normal catagen transition and prematurely jump into telogen. Subsequently, these follicles may attempt to restart the cycle but produce only poor-quality, weak hair fibers in what researchers term a “dystrophic anagen state.” Examination of fallen hairs reveals telogen roots, confirming this abnormal cycle disruption.

Microscopic Changes: Pathology of Alopecia Areata

Under microscopic examination, alopecia areata reveals characteristic inflammatory changes. Lymphocytic infiltrates and granulomatous inflammation surround late anagen hairs and penetrate hair follicles during acute disease phases. The inflammatory infiltrate consists mainly of activated T lymphocytes, accompanied by CD4 cells and Langerhans cells, confirming the autoimmune nature of the condition.

Interestingly, nail changes in alopecia areata correlate with specific alterations in the proximal nail matrix, visible through both light and electron microscopy techniques. This connection explains why nail abnormalities often accompany severe hair loss cases.

Clinical Presentations: Recognizing Different Patterns

Classic Patchy Pattern

Most patients initially present with round or oval bald patches measuring 1-2 centimeters in diameter. These patches can appear anywhere on hair-bearing skin but most commonly affect the scalp. The patches may remain isolated or increase in both size and number as the condition progresses.

Progressive Patterns

Alopecia Totalis: Complete loss of terminal scalp hair represents a more severe form requiring aggressive intervention.

Alopecia Universalis: Total loss of all body hair, including scalp, facial, and body hair, constitutes the most severe manifestation.

Ophiasis Pattern: This distinctive band-like pattern affects the parietal and occipital regions, often indicating a poor prognosis and treatment resistance.

Diagnostic Clues

Several clinical features help confirm the diagnosis. The affected scalp usually appears completely normal, without scaling, redness, or scarring. The pathognomonic “exclamation mark” hairs appear particularly at patch peripheries—these short, broken hairs have broader distal ends than proximal ends, illustrating the disease’s characteristic follicular damage sequence.

A fascinating aspect of alopecia areata involves its selective targeting: the condition affects only pigmented hairs while sparing unpigmented or white hair. This selectivity sometimes creates striking patterns where gray or white hairs remain in otherwise bald areas.

Associated Nail Changes

Nail involvement occurs in approximately 10% of referred patients, manifesting as fine pitting, mottled lunula, or trachyonychia. Trachyonychia gives nails a rough, sandpaper-like quality with longitudinal ridging and occasional distal edge splitting.

Diagnostic Approach and Differential Diagnosis

Currently, no definitive diagnostic test exists for alopecia areata. Dermatologists rely on clinical pattern recognition, lesion examination, and hair pull tests for diagnosis. When uncertainty exists, skin biopsy provides confirmatory evidence through characteristic inflammatory patterns.

Key Differential Diagnoses

Tinea Capitis: Fungal scalp infections typically show obvious inflammation with scaling and pustules accompanying patchy hair loss.

Trichotillomania: This anxiety disorder involving compulsive hair pulling rarely creates complete baldness, and broken hairs remain firmly anchored in the scalp, unlike the loose exclamation point hairs of alopecia areata.

Early Scarring Alopecia: Progressive scarring conditions eventually destroy follicles permanently, creating smooth, scarred areas.

Secondary Syphilis: The “moth-eaten” alopecia pattern of secondary syphilis can resemble diffuse alopecia areata but occurs in the context of other syphilis symptoms.

Diffuse alopecia areata presents particular diagnostic challenges, potentially mimicking other causes of diffuse hair loss including thyroid abnormalities and other autoimmune diseases. The rapid progression typical of diffuse alopecia areata usually clarifies the diagnosis over time, though biopsy may be necessary in uncertain cases.

Prognosis: Understanding Treatment Expectations

Favorable Outcomes

Spontaneous remission occurs relatively frequently when hair loss remains limited to a few small patches. These limited cases often resolve without intervention, making conservative observation a reasonable initial approach.

Challenging Cases

Extensive alopecia areata carries a less favorable prognosis, with fewer than 10% of patients achieving spontaneous recovery. Several factors predict poor outcomes:

- Childhood onset

- Loss of body hair beyond the scalp

- Nail involvement

- Concurrent atopic conditions

- Positive family history for alopecia areata

- Ophiasis pattern

Understanding these prognostic factors helps clinicians set realistic expectations and choose appropriate treatment intensities.

Management Strategies: From Conservative to Cutting-Edge

Conservative Management

All currently available treatments for AA have a high failure rate and none alters the natural history of the disease. “No treatment” is a legitimate option in patients with a short history and limited disease, in view of the high rate of spontaneous remission in this group.

Topical Corticosteroids

These medications work through strong inhibitory effects on T lymphocyte activation. Commonly prescribed agents include flucinolone acetonide cream, betamethasone dipropionate cream, and clobetasol propionate. The typical regimen involves twice-daily application for two weeks initially, continuing until cosmetically acceptable regrowth occurs or for a minimum of 3-4 months.

Side effects include local folliculitis appearing after several weeks of treatment, along with potential telangiectasias and local skin atrophy with prolonged use.

Intralesional Corticosteroids

Intralesional corticosteroid injections represent the most effective approach for treating patchy alopecia areata. Hydrocortisone acetate (25mg/ml) and triamcinolone acetonide (5-10mg/ml) are commonly used agents delivered through subdermal scalp injections.

Treatment protocols typically involve injecting 1-3 ml per session with individual injection volumes of 0.05-1ml, repeated every 4-6 weeks as needed. Initial hair regrowth becomes visible within 4-8 weeks. However, this injection method proves inappropriate for rapidly progressive or extensive disease.

The main risk, particularly with triamcinolone injections, involves significant skin atrophy potential that increases exponentially with repeated injections.

Systemic Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids can induce short-term hair growth in alopecia areata patients, but regrown hair typically disappears after treatment discontinuation. Newer pulsed regimens show promise: prednisolone 200mg once weekly for three months or dexamethasone 5mg daily for two consecutive days weekly for three months.

Unfortunately, most patients require continued treatment to maintain hair growth, and the response usually proves insufficient to justify the associated risks.

Minoxidil: Topical and Oral Options

The 5% minoxidil solution works by relaxing arteriolar smooth muscle and causing vasodilation, with hair growth effects occurring secondary to improved blood flow. No more than 25 drops should be applied twice daily regardless of affected area extent. Initial regrowth becomes visible within 12 weeks, but continued application remains necessary for maintaining cosmetically acceptable results.

A spray formulation (Minoxin spray) offers convenient application: 1ml with dropper or sprayer (6 sprays) applied directly to clean scalp twice daily, followed 30 minutes later by topical corticosteroid ointment application.

Response rates vary from 8-45% in patients with extensive disease (50-99% hair loss). Side effects include distant hypertrichosis (5%) and local irritation.

Anthralin (Dithranol)

Although its mechanism remains unclear, anthralin’s hair growth properties likely relate to its irritant properties and ability to cause non-allergenic inflammatory dermatitis. Treatment involves applying the medication sparingly to affected areas, typically as short-contact treatments lasting several hours depending on cutaneous irritation tolerance, then washing off with soap and water.

Adverse effects include pruritus, erythema, scaling folliculitis, local pyoderma, and regional lymphadenopathy. Temporary treatment cessation for several days allows rapid adverse effect resolution, after which treatment can resume with shorter contact periods.

Photochemotherapy (PUVA)

PUVA therapy involves taking psoralens approximately two hours before measured long-wave ultraviolet light exposure. Hair regrowth initiation may require 40-80 treatments with complete regrowth taking 1-2 years.

The high relapse rate following treatment necessitates continued therapy to maintain hair growth, potentially leading to unacceptably high cumulative UVA doses.

Contact Immunotherapy

This approach involves sensitizing patients to potent allergens, usually diphenylcycloprenone (DPCP) or squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE), then applying weekly scalp solutions adjusted to induce mild dermatitis reactions.

Approximately 30% of extensive alopecia areata patients achieve cosmetically worthwhile responses after six months of treatment. Continuous or intermittent treatment maintains responses in some patients. Alopecia totalis and universalis respond less favorably to contact immunotherapy.

Risks include severe dermatitis, urticaria, and pigmentary abnormalities including vitiligo.

Revolutionary JAK Inhibitors

Janus kinase inhibitors have changed the treatment landscape, making treatment of moderate-to-severe disease possible. Baricitinib and ritlecitinib are approved, deuruxolitinib is advancing toward approval.

These medications represent the most significant advancement in alopecia areata treatment, offering hope for patients with moderate to severe disease who previously had limited options.

Cosmetic Management

Female patients with extensive alopecia areata often choose wigs or hairpieces for aesthetic restoration. Wigs prove less successful in men, who often prefer alternative approaches like complete scalp shaving. Temporary tattooing can help restore eyebrow appearance when facial hair loss occurs.

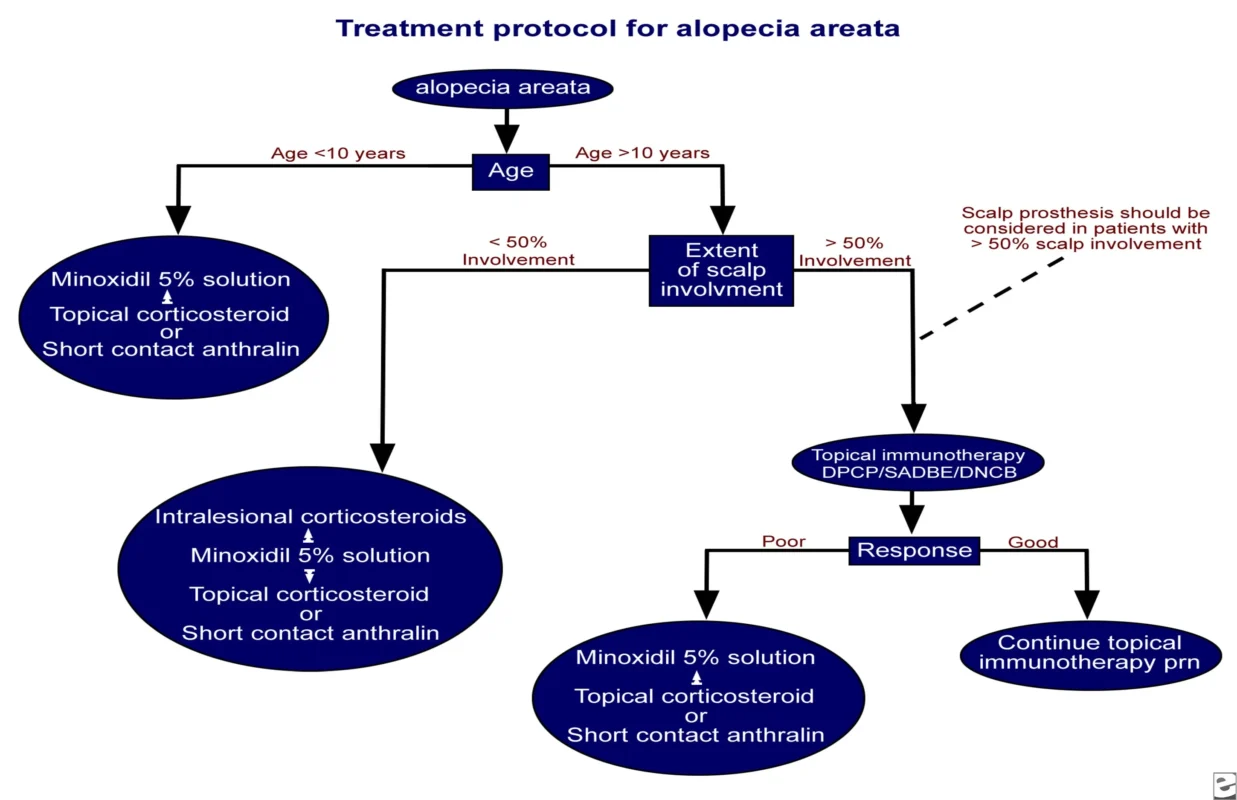

Treatment Algorithm: A Systematic Approach

Modern treatment protocols follow age and severity-based algorithms:

For patients under 10 years: Minoxidil 5% solution, topical corticosteroids, or short-contact anthralin represent first-line options.

For patients over 10 years: Treatment selection depends on scalp involvement extent:

- Less than 50% involvement: Intralesional corticosteroids, minoxidil 5% solution, topical corticosteroids, or short-contact anthralin

- Greater than 50% involvement: Topical immunotherapy with DPCP, SADBE, or DNCB

Response evaluation determines subsequent management, with poor responders receiving alternative topical therapies and good responders continuing successful treatments. Scalp prostheses should be considered for patients with greater than 50% scalp involvement.

Dispelling Common Myths

Patient education must address prevalent misconceptions about alopecia areata:

- Combing hair does not weaken hair follicles

- Hats and wigs do not cause alopecia

- Daily hair washing does not increase hair loss

- Excessive scalp sweating does not cause hair loss

- Short haircuts do not strengthen follicles

- Shaving does not cause thicker hair regrowth

- Frequent shampooing does not contribute to alopecia

- Dandruff does not cause permanent alopecia

- Alopecia areata does not exclusively affect intellectuals

These myths can prevent patients from seeking appropriate treatment and following evidence-based management strategies.

Conclusion

Alopecia areata management has evolved dramatically with improved understanding of disease mechanisms and development of targeted therapies. While complete cures remain elusive, modern treatment approaches offer significant hope for hair regrowth and improved quality of life. Success requires individualized treatment selection based on disease severity, patient age, and prognostic factors, combined with realistic expectation setting and comprehensive psychosocial support.

The integration of traditional therapies with emerging treatments continues expanding therapeutic options for this challenging autoimmune condition. As research progresses, future developments promise even more effective interventions for patients struggling with this life-altering disease.